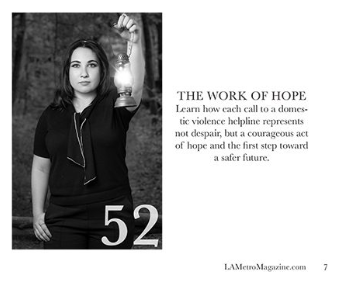

The Work of Hope

This article appears in the Q1 issue of Maine’s LA Metro Magazine.

Make no mistake, the work at any domestic violence resource center (or DVRC), is not easy. But what many people fail to realize at first glance is that this work, at its core, is profoundly and unapologetically hopeful.

When people hear that I work for a domestic violence and sex trafficking resource center, the response is nearly universally the same. It is “That must be so hard.”

“Some days,” I usually say. “But it’s good, too. It can be happy.”

At a recent staff meeting, our team discussed a TEDx talk called “The Science and Power of Hope,” and how it resonated with us and our work. In it, Dr. Chan Hellman discusses research on “hope theory”, and how an individual’s ability to cultivate hope can be affected by adversity and trauma. Hope, as Dr. Hellman defines it, “is the belief that your future will be better than today and that you have the power to make it so.” It is unique from optimism – believing your future will be better than today – because hope requires that you feel agency in making that better future a reality.

Many of our staff members related to this definition of hope and connected it to the work we do with survivors of domestic abuse, sex trafficking, and sexual exploitation. Our DVRC supports nearly 3,000 survivors each year in our catchment area, working with them to do safety plans, danger assessments, and set goals on their way to living an independent, abuse-free life. These activities might not typically be thought of as issues of “wellness,” but truly, safety and independence are at the heart of the concept. They allow an individual the autonomy to pay attention to their body and mind, to prioritize their health, and to make changes to improve their life. Hope is a vital part of that formula.

Despite what may look like difficult or depressing work from the outside, within the domestic violence prevention movement, most advocates would agree that every call to a domestic violence hotline is hopeful. That’s because every call to a Helpline is person who sees that there can be – there must be – a better future for themselves. They pick up a phone and call a stranger to talk about that hope for a better future and make a plan to create it. Each time a survivor calls, advocates on the other end of the line are there to help cultivate that hope – and the belief that each one of those callers can have power and agency to bring their own hope to realization.

Personal agency – the ability and confidence to make your own decisions – is an important part of the process of escaping abuse or exploitation. Staff at DVRCs are trained in how to help, support, and advocate, but we are also trained in how to keep the process centered on the survivor themselves – what they want, and their ability to achieve the goals they set. How else would a person build confidence, resilience, and the belief that they have the power to improve their situation? These things are the underpinnings of our work.

Does the caller always feel hopeful at the outset? Perhaps not. They are often navigating trauma, violence, and abuse so extensive that they are no longer sure of who they are as an individual – their life having been so consumed by the identity, needs, and demands of their abuser. Many have lost touch with what wellness and joy look like for themselves, because it’s been buried under what an abuser has demanded of them. By making that call, they have taken an incredibly brave first step toward creating an autonomous life – the life they want. Domestic violence response advocates know, after working with thousands upon thousands of survivors over nearly fifty years since the movement began in earnest, that the first call is the hardest one for a survivor to make, and it is the beginning of a relationship between that survivor their advocates that may continue for weeks, months, or years. We’ll talk about safety plans, danger assessments, and tools of the civil and criminal legal system that might help them. They might set up security cameras or find a new apartment. We’ll also talk about what kind of home they want to create for themselves. We’ll talk about re-learning what they love to cook, or what their favorite scents are, or what kinds of music they like to listen to. Each of these rediscoveries strengthens a survivor’s resolve to focus on themselves and what they can achieve, despite the barriers they may face, rebuilding a sense of resilience.

In Dr. Hellman’s talk, he shared a few key findings about how hope functions within the framework of trauma, many of which our team connected with. They include:

People living within trauma are more likely to set avoidance goals than achievement goals. Meaning they will set a goal to avoid something (“I will not eat fast food this week”) rather than to work toward achieving something (“I will learn to make my own pesto”).

Goals are the cornerstone of hope, and they are more successful at instilling hope and resilience if they are achievement-based.

Two of the primary tools we need to achieve goals are pathways – the ability to both identify routes toward goals as well as problem solve around obstacles if needed – and perseverance, which is the ability to sustain motivation along those pathways.

Trauma and adversity make it more difficult for your brain to problem solve and form a pathway out of a problem or situation. And willpower, of course, is finite, and it is drained by fear and worry.

What is an advocate to do – and how are they themselves able to maintain hope – when they are faced with the above obstacles present in nearly every survivor’s life? Their experience with, and knowledge of, pathways and their ability to persevere are key.

We often use the phrase “to come alongside survivors” when we talk about our work. Imagine you are walking alone on a forest path. It’s rocky and dim, with shadows making tree roots hard to see, so they snag at your feet. Maybe you knew this hiking path at the beginning, but you got a little turned around, and you’re worried you won’t find your way out before nightfall. Your senses are in overdrive, trying to discern every sound to see if it means danger or every landmark to see if it looks familiar. It’s scary and stressful and exhausting, and you say, “I just need help.”

Imagine if, rather than speaking that need to an empty forest, what you hear is “I have a map.” The mapholder tells you they’ll stay with you until you’re safely out of the forest. They tell you not to worry if it gets dark, because they have flashlights in their pack. Their phone is fully charged and has signal. They’re familiar with these woods and can confirm you’ve been going the right way, you just needed some more time. They offer you a snack, some water, and ask if you want them to walk with you the rest of the way.

The walk out of those woods looks very different than it would have if you had been left to navigate that unfamiliar path alone, exhausted, and panicked. That is what we think of when we say that advocacy is us coming alongside a survivor. We’re not there to rescue them, to call in a helicopter to pick them up, or pull them down a different path. We’re there to walk with them and, maybe, carry the flashlight.

Hope, says Dr. Hellman, is a social gift. Our connectedness with each other is one of the single best predictors of hope and wellness. This may have been the part of his TedX talk that our staff connected with the most. So much of an abuser’s work is to isolate – to pull a survivor away from their natural supports, those emotional and social handholds that could help pull them out of abuse, away from those things and people that enhance their wellness. This may involve controlling who they can talk to, monitoring their text messages, insisting on joint bank accounts so they may track spending and control the financial resources. Nearly always, it involves systematic undermining of a survivor’s intelligence, judgement, instincts, and memory. In short, all of the things they would need to rely on if they were to create a pathway out of abuse – all of the things that keep us hopeful.

The social nature of hope and wellness is the bedrock of advocacy. It is an advocate’s ultimate task to reaffirm a survivor’s belief that their life can and should be better, and then to inject hope in the form of validation, safety planning, reassurance, help navigating systems, and acceptance of that survivor’s lived reality. Importantly, advocacy is not overlaying our own goals onto a survivor’s experience. On the contrary, advocates continually check in with the survivors they are working with to re-affirm the goals that survivor has set and assure that the advocate’s work is in support of those goals. This kind of wellness begins with asking yourself simply what makes you happy, what makes you thrive, and what makes you feel better?

“Hope is a goal and a plan to get there,” one staff member said at our meeting. Survivors may not know the goal when they call. They know something is wrong and they want it to change. It is through the one-on-one advocacy provided by DVRCs that a survivor can begin to ask “What do I want?” This is a question they may be asking themselves for the first time in many years, and it’s often at the heart of our interactions with them. Once they can answer this question for themselves, having an advocate alongside them is paradigm-shifting, because they are no longer creating that pathway alone. While they rebuild the problem-solving skills and the willpower reserve that have been weakened by trauma, they have a supportive person available who is there to offer options, discuss ways forward, and then let them decide what is best and be a support for that decision. Through fits and starts, our advocates see survivors shift their goals and plans from those within a trauma framework to those beyond it – from goals aimed at avoiding further trauma to goals that pursue liberation, or from planning for short term survival to thinking about long term happiness. Survivors have to take that first step to get to the last step.

Dr. Hellman shared that hope and success lead to more hope. When a person learns a task for the first time, like parallel parking a car, they gain hope they can complete that task again and maybe learn even more new driving skills. They may be able to teach others that same skill someday. The discovery that they have the ability to do things they’ve never done before, and succeed at those things, and share their skills and knowledge with others, is ultimately why we believe that domestic abuse and sex trafficking prevention is deeply hopeful work. Advocates at DVRCs understand that every time we work with one survivor, we are working to instill hope not only for that person, but for our communities at large. Every survivor who is able to rebuild their capacity to hope, their ability to create a pathway to happiness, and their willpower to walk that path, might then be able to help another survivor do the same. Survivors benefit from this, but so do our advocates, who both create that cycle of hope and are sustained by it. Our communities benefit, because every person living free from violence is a boon to our community health.

A year ago, our workplace revisited and updated our mission statement to add vision and values statements as well. Our mission – to provide person-to-person, individualized advocacy to survivors and engage our communities in social change – remained largely the same. But our vision statement – to endeavor to build safe communities in which everyone is free from abuse and exploitation – allowed us to formalize the centrality of hope and community-wide wellness as well as state unequivocally that our work is not only responding to abuse and exploitation, but also in envisioning and striving for a society in which those experiences do not exist. This work can be hard, but when you reframe it in that way, it becomes something entirely different. It becomes the work of hope.